|

|

|

|

|

|

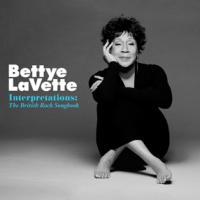

| BETTYE LAVETTE : : INTERPRETATIONS:THE BRITISH ROCK SONGBOOK |

|

Produced by Bettye, Rob Mathes and Michael Stevens, INTERPRETATIONS is a 12-song journey through compositions by the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Traffic and Pink Floyd, among others, before concluding right where the very idea for the new album started: Bettye's visceral show-stopping rendition of The Who's "Love Reign O'er Me" from the 2008 Kennedy Center Honors, which appears here as an extended bonus track.

Click for more

|

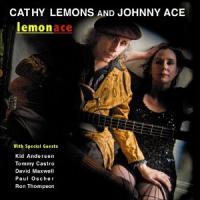

| CATHY LEMONS AND JOHNNY ACE : : LEMONACE |

|

Veteran blues bassist and master showman Johnny Ace teams up with Texas-born blues singer Cathy Lemons to lead a stellar cast through a soulstirring set of original music that draws on their deep musical backgrounds and left-of-center sense of humor. Lemonace band members Pierre Le Corre (guitar) and Artie "Stix" Chavez (drums) are joined by special guests Tommy Castro, David Maxwell, Kid Andersen, Paul Oscher and Ron Thompson.

Now living in San Francisco, Cathy and Johnny have both paid their dues, in full. Cathy started out by honing her chops with Texas bluesmen such as Anson Funderburg, and even performed with Stevie Ray Vaughan. In the 1980’s she came to California and toured with John Lee Hooker as his sendoff singer. She’s been headlining her own bands since then and has come full circle as a fully developed singing stylist, writer and lyricist. Johnny, originally from New York City, has played with a who’s who of blues giants including John Lee Hooker, Otis Rush, Charlie Musselwhite, Victoria Spivey and countless others.

|

Lamenting The Future Of the Blues

|

| (Jim Fusilli/WSJ.com) In early May, I traveled to Memphis to attend the Blues Foundation's 31st annual two-day gala, which included its Hall of Fame induction ceremony and awards banquet. Buddy Guy received a Lifetime Achievement Award. Pinetop Perkins, now 96 years old, turned up, as did 80-year-old Bobby "Blue" Bland and 78-year-old Hubert Sumlin. I heard folk blues, country blues, jump blues, Chicago blues, Delta blues, Texas blues, fast blues, slow blues, good blues and bad blues. What I didn't hear was new blues, and I flew back home no less relieved of my own blues over the genre's troubling future.

Today's blues music isn't only steeped in the past; it's anchored to it. During the performances before and during the banquet, I could trace to almost every song, instrumental solo or vocal style I heard its originator or its most celebrated proponent—and I'm far from an expert on the history of the blues. These tales of heartache, oppression and fleeting joy sounded all too familar.

According to Jay Sieleman, the Blues Foundation's executive director, most blues fans aren't looking for something new. "We all don't want the blues to be the same ol', same ol'," he said, "but it'd better be close."

For those blues afficionados, the music is the common bond of a social scene, at blues festivals and cruises, featuring famous artists who play and then meet fans. The high spirits at these events can create the impression that the blues is still a thriving and growing art form. It is not.

"The blues is getting to be like an endangered species," Mr. Guy said by phone. "It's like somebody put a spell on it."

The 73-year-old Mr. Guy was talking about the paucity of radio airplay for the blues, but he might as well have been discussing the blues as contemporary popular music. Young fans who still fuel the music marketplace may admire veterans like Mr. Guy, but they're right to ask if there's a new way to play the blues, one that's affiliated with new sounds and styles. On disc, the rapper Nas riffed on Muddy Waters's "Mannish Boy" in his song "Bridging the Gap" and Chris Thomas King married hip-hop and the blues on his album "Dirty South Hip-Hop Blues," but that sort of experimentation isn't encouraged. When people in the blues establishment talk about new artists, they usually mean young musicians who work in an old style, like those who play jug-band music or pay homage to the Mississippi Sheiks. If you can sound like Stevie Ray Vaughan on electric guitar, you can find a place in today's blues world.

In 2004, Skip McDonald, who works under the name Little Axe, released "Champagne and Grits," which mixed traditional blues with spoken word, drum loops, Indian percussion and a dab of reggae. It was the kind of album that could bring young listeners to the blues: Give it to a Citizen Cope or a Massive Attack fan and they'd feel at home. It wasn't well received by the blues community.

"I upset a lot of people," Mr. McDonald told me. "People are so traditional in their approach. It was a hybrid amalgamation, but the blues was my first stop."

The blues establishment seems to have little interest in reaching out to other musical communities. No rock, hip-hop or jazz artists with a musical debt to the blues were part of the activities in Memphis. Perhaps in turn, blues musicians aren't invited to participate in most major rock festivals: There were no traditional blues artists at this year's Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival, nor will there be any at the Glastonbury Festival in Britain later this month. At this weekend's Bonnaroo Music & Arts Festival in Manchester, Tenn., only Trombone Shorty and Big Sam's Funky Nation, both from New Orleans, and the string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops, adhere to blues traditions.

But many artists on the Bonnaroo bill who draw from the blues—the John Butler Trio, the Black Keys, the Dead Weather and Galactic, among them—have the kind of younger audience from which the blues as a commercial entity could benefit.

"We're all worrisome about getting a young audience," XM Satellite Radio's Bill Wax said over sweet tea in Memphis. At the same time, though, he said: "I don't believe the blues world looks for the next big thing. We love people who play around with the form, but we don't want people to mess with the tradition."

For the blues to have a future in which daring artists bring in new listeners, the establishment needs to share the blues with people who have a different idea of what it is. The future can be built on new modes of expression if musicians and fans remember the blues isn't merely a form. It's a feeling. Capture it, as so many artists did in decades past in so many ways, and you're playing the blues, whether it's with a bottleneck, a big band or a studio full of digital effects.

Jason Moran, the gifted jazz pianist who eagerly explores the blues, explains how he connects with a feeling necessary to make authentic music: "I remember saying to an older musician that I wanted to play bebop, and he said, 'You can't. You didn't live in that time.' That really fired me up to think about what was going on in that time to make those musicians play that way."

As for Mr. Guy, he profited from some outreach when his daughter Shawnna asked him to appear on "Block Music," her 2006 platinum album. "It's a new thing, a different way," Mr. Guy said of the rap-blues marriage. "Like when Muddy put electricity to the harmonica."

|

BLUES IN THE BLOOD FRIDAY AT IH MISSISSIPPI VALLEY BLUES FESTIVAL

|

|

The 26th annual IH Mississippi Valley Blues Festival is sure to be the best bang for your blues buck. With three-day festival passes only $25, attendees will enjoy 28 acts performing the best in contemporary and traditional blues in the world—for less than $1 per act.

IH Mississippi Valley Blues Festival runs July 2 – 4, at LeClaire Park—a blues-inspiring outdoor venue located at the crossroads of U.S. Route 61 and the Mississippi River—in Davenport, Iowa.

The festival kicks off with “Blues in the Blood” Friday. All eight acts performing that day include descendants of blues legends. Artists playing Friday include Muddy Waters’ son, Mud Morganfield; B.B. King’s daughter, Shirley King; Luther Allison’s son, Bernard Allison; Pinkney “Pink” Anderson’s son, Little Pink Anderson; Johnny Shines’ daughter, Caroline Shines; Carey Bell’s son, Lurrie Bell; Big Daddy Kinsey’s three sons, Donald, Ralph and Kenneth Kinsey of The Kinsey Report. Lil’Ed and the Blues Imperials will headline Friday night’s show. Lil’ Ed Williams is the nephew of J.B. Hutto.

“The blues run deep in the blood of the artists playing Friday,” notes Karen McFarland, MVBS vice president. “They come from legendary blues families, and all are incredible artists in their own right.”

Other featured artists playing the festival include The Legendary Rhythm & Blues Review with Tommy Castro (winner of four 2010 Blues Music Awards), Debbie Davies, Magic Dick and Sista Monica; Ruthie Foster; Billy Branch & the Sons of Blues; and The Nighthawks with Hubert Sumlin.

For more information about the festival, the full lineup of artists, ticket locations, transportation and lodging, please visit www.mvbs.org or call 563-32-BLUES

|

This New DAWG's Got The Blues For Ottawa

|

| EMC Entertainment - Radio in Ottawa is going to the DAWGs and for those who love blues music, nothing could be finer.

As of Monday June 7, CIDG-FM, branded as DAWG FM, is on the air as Canada's only blues and blues-rock radio station. Owned by Frank Torres and Ed Torres of Skywords Traffic Network, the station is broadcasting at 101.9 FM in Ottawa.

DAWG FM was officially launched with a gala at Tucson's June 1. The opening party was full of praise for everyone who has worked hard to make the station a reality.

"We are a small broadcasting company with a passion for radio and a passion for the blues," said Ed Torres. "Our company is all about family...everyday I go to work with my brother, how good is that?"

DAWG FM was licensed by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) on Aug. 26, 2008, only to have the licence sent back for reconsideration. Frank and Ed Torres launched an exhaustive and expensive year-long campaign to have the licence upheld and to pave the way for all-blues radio formats across Canada. In August 2009, the CRTC re-issued the licence for DAWG FM.

"The appeal of the first licence was emotional and exhausting. It's unfortunate that we've been delayed almost a full year," said Ed Torres. "Democracy isn't always efficient, but in the end it works. The CRTC has acknowledged that blues is not just an essential North American art form, but that it can be the basis of a financially viable commercial FM station."

As part of the reconsideration, the CRTC also issued a licence to a group of Franco-Ontarians that launched the appeal.

The New 101.9 DAWG FM will play a combination of blues-rock, traditional blues, rhythm and soul and will feature a wealth of Canadian talent.

"Ottawa is the perfect flagship market for DAWG FM's music format," said Frank Torres. "Along with Ottawa 's world class blues festival, DAWG FM will help make Ottawa 'Chicago North' - a focal point for Canadian blues artists to get their music played on FM airwaves".

In a letter to the Ottawa Citizen March 18, Torres outlined his philosophy for the station.

"The current state of Ottawa radio is the very reason we decided to apply to the CRTC for an FM licence. Corporate consolidation has led many large broadcasters to target audiences by demographic and gender. Play lists are built by U.S. consultants, decisions are made in far away boardrooms and as a result we are left with formulaic, homogenized radio."

To ensure DAWG FM stays true to blues and Canadian content, announcers are familiar with the local music scene. Geoff Winter and Laura Mainella will host the "DAWG's Breakfast" morning show.

"I am very excited to be returning back to my roots!" says Winter after working as a radio host in Florida for the past 10 years. "I am thrilled to be working with a great team of people and playing the music I love! This is going to be an exhilarating time in Ottawa radio and I'm pleased to be a part of it." Winter helped to build CHEZ FM's audience after it launched.

Co-hosting is Mainella, a 20-year on-air veteran known for her dynamic, outspoken personality.

"I am fortunate to be given the opportunity to work with such a motivated team. Ottawa artists have been longing for a supportive, engaging forum to showcase their talent. Throw us a bone and we promise not to disappoint."

Operations Manager Yves Trottier is proud of DAWG's talented on-air team.

"Geoff and Laura's styles compliment each other very well and they are a great fit for the station's sound. We are confident that DAWG FM will have an immediate impact on the Ottawa market."

101.9 DAWG FM will target adults aged 25-54, with a core demographic between 35 and 54. DAWG FM will play the artists such as Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jeff Healey, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Colin James, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Van Morrison. Local bands, such as Monkey Junk and J.W. Jones, will also top the play list.

The decision to go all-blues is one that reflected market research.

"We looked at the Ottawa market for which types of music formats were under-represented or not served, " says Torres. "Ottawa's a huge, huge blues town with one of the largest blues festivals - Bluesfest - but there are no blues stations whatsoever.

"So we did some market research, and it came back very positive for the market to sustain an all-blues station."

Torres also says he's been very encouraged by the response of advertisers.

"It's somewhat overwhelming," says Torres. "We've had a lot of people tell us this is what will bring them back to radio."

Torres said DAWG may have a lot to prove, but his organization is up to the challenge.

"You can't get this far without a lot of people believing in this. We are a full-service radio station, and our background is marketing, so we're going to change the rules on how you market radio stations in Ottawa."

Station manager Todd Bernard emphasized that DAWG FM will remain a close-knit family, with tight ties to the community.

"DAWG FM is not just about the music," he said. "Local information is just as important. Local and major and minor league sports, news and traffic will be the forefront of our information. DAWG FM will be a part of the community. Through our spoken word content, our music and our devotion to local organizations and fundraising, DAWG FM will be there for the people of Ottawa."

The company has also created a website called Blues in Canada.com "to provide a virtual meeting place to unite Blues lovers across Canada and around the world. It is the home of 101.9 DAWG FM, Canada's first and only all Blues radio station."

In addition to DAWG FM, Ed Torres and Frank Torres are the principals of Skywords Radio and Media companies, a national radio broadcasting organization with offices in Halifax, Ottawa, Markham and Edmonton.

|

Music Your Way: Stretching the Limits

|

| 1)MIXMASTER Korg’s Kaossilator has 100 preloaded tones and patterns to turn into songs.

2)SWEET SOUNDS The Bowers & Wilkins Zeppelin Mini is for small spaces and uses technologies from the company’s top-end speakers

(Jason Turbow-NYTimes) It's June, and you want to give the gift of audio to the father in your life, or the new graduate or your neighbor who has a fondness for Flag Day

The thing is, you’re Appled out. Between the iPod crunch and iPad craze, you feel as if everybody you know already has an iProduct with which to listen to Lady Gaga as they deadhead the geraniums.

You want to offer something different, to provide a new arena of auditory bliss.

We’ll do you one better: many products augment the iPods your loved ones (and neighbors) already own. Now go make people happy.

B&W ZEPPELIN MINI An iPod dock — an independent speaker unit to which an iPod can be attached for headphones-free playback — brings a new level of utility to everyone’s favorite device. The majority of docks, however, are small, tinny boxes that, while functional, hardly augment the music being played.

When Bowers & Wilkins, long known for quality speakers, came out with the Zeppelin dock in 2006, it was a watershed moment of high-end design for the category. The Zeppelin, however, has two main drawbacks: it takes up more space than most docks, and at $600, it isn’t cheap.

Enter the Zeppelin Mini. Priced at $400, it is made for desktop spaces and offers many of its big brother’s features. It also includes some technologies used in the company’s top-end $60,000 Nautilus speakers, said Jennifer Cole, director of marketing. A U.S.B. cable also allows the unit to serve as an elegant computer speaker. www.bowers-wilkins.com

PIONEER XW-NAV1K-K HTD Where the Zeppelin Mini does one thing — reproduce sound — exceedingly well, Pioneer looks to cover as many bases as possible with this dock, essentially turning it into a home theater system.

It plays music directly from an iPod and connects to a TV to display associated video. It features a DVD player to further take advantage of the TV connection, and a CD player to listen to music and copy MP3s to a U.S.B. drive. Just in case that’s not enough, there’s also an FM tuner.

“This unit isn’t designed to replace the main home theater, but it’s a great second-room application,” said Chris Walker, director for audio-video marketing and product planning for Pioneer. “A lot of times I have stuff on my phone that I want to show to people, but looking at something on a 4-inch screen is difficult. If I have this hooked up to TV, I can show whatever I want, right through the dock.” It is priced at $299. www.pioneerelectronics.com/PUSA

SINGING MACHINE ISM1028 Taking the concept of the iPod dock in a completely different direction, the Singing Machine brings us what is effectively iKaraoke. Head to iTunes for a selection of hundreds of sing-along albums and songs (or sample from the 7,000 songs made available by the company), plug your iPhone into the ISM1028, and away you go.

This is a free-standing machine, with tower speakers and a 7-inch LCD screen — a “furniture piece,” according to Bernardo Melo, vice president for global sales and marketing for SMC Global. (Being an all-in-one system is primarily what sets it apart from the $99 ISM370, which must be hooked up to a television for video.) Priced at $299. www.singingmachine.com

STANTON T.55 U.S.B. TURNTABLE So your father insists on playing classic cuts from his vinyl record collection, and you’re shocked to find out that he knows a thing or two about music from back in his day. Inquire about playing it digitally, however, and he’s struck mute.

Stanton, known primarily for its D.J.-quality turntables, holds the patent on U.S.B.-enabled record players that plug into a computer and offer quick digitization of whatever is spinning for playback on your iPod or other digital audio device. (The T.55, priced at $199, is the belt-drive model; the higher-end T.92 offers direct drive.)

Included software allows not only for simple transfer, but for easy editing of pops and clicks that might pass through the needle during playback.

The unit comes with the Stanton 500.v3 cartridge, which by itself sells for $50. “That makes a huge difference in the quality of the audio you’re recording,” said Dan Bruck, head of marketing for Stanton. “In this price range you don’t normally get a high-quality cartridge included — you get a knock-off Chinese cartridge that doesn’t give you full frequency. The cartridge we include circumvents that.” www.stantondj.com

KORG KAOSSILATOR If nothing else, the iPhone has proved that people are willing to use their commute time each morning looping and layering preloaded tones into custom-built songs. The Kaossilator is essentially an anti-iPod — a surprisingly beefy music-making device, the functions of which are approximated by a number of iPhone apps. (Any app, however, would be hard-pressed to match this level of robustness.)

The Kaossilator offers 100 preloaded tones and patterns — from crazy electronica to lead trumpet to drum sounds — each of which is manipulated via touchpad. Every tone can be structured according to one of 31 different scales (chromatic, major and minor blues, Gypsy and even three ragas), meaning that no matter what you do on the touchpad, you’ll never strike a wrong note.

Simple controls allow for manipulation of tempos, and the looping feature lets users replay snippets ad infinitum across multiple layers’ worth of sound. Output jacks allow for amplification. This year, give the dad in your life the gift of creativity on his train ride to work. Priced at $199. www.korg.com

|

CHICAGO BLUES FESTIVAL THIS WEEKEND

|

| The Chicago Blues Festival this weekend in Grant Park celebrates the life and music of Howlin' Wolf on the centennial of his birthday with special performances and jam sessions.

The internationally acclaimed festival is designed to celebrate and remember the blues tradition and heritage. The 3-day festival features five distinct stages that tell the story of the Blues using various Blues music styles. .

The Blues Fest is the largest free blues festival in the world and remains the largest of Chicago's Music Festivals. The 27th annual festival opening Friday is expected to attract more than 640,000 blues to prove that Chicago is the "Blues Capital of the World." Past performers include Bonnie Raitt, Ray Charles, B.B. King, the late Bo Diddley, Buddy Guy and the late Koko Taylor. This year's festival will feature Chicago's hometown favorites and performers from around the country. The line up includes: Corky Siegel, Dave Weld and The Imperial Flames, Eddie Shaw and the Wolf Gang, Hubert Sumlin, Sam Lay, David "Honeyboy" Edwards, Billy Boy Arnold, Grady Champion and dozens more.

Blues Fest will be held Friday through Sunday from 11 am to 9:30 pm in along the city's lakefront in Grant Park at Jackson and Columbus. For a complete schedule and information on related events, visit: www.chicagobluesfestival.us/ or call or call 312-744-3370.

|

A Lament for the Blues in Their Backyard

|

| The blues player Buddy Guy, with Mayor Richard M. Daley, on May 27 outside his new club.

Buddy Guy said he was worried about the blues.

(JessicaReaves/NYTimes.com) He worried even as he oversaw the finishing touches on the new location of his club, Buddy Guy’s Legends, which is part musical venue, part museum. He is worried that his club cannot provide enough exposure for all the musical talent that comes through Chicago, and worried that young people are not exposed to the music he has loved all his life.

He is worried, in short, that the city’s long, proud reign as the world’s unequivocal blues capital might be fading into memory.

When Mr. Guy arrived here in 1957, it was the heyday of Chess Records, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, and there seemed to be a blues venue — like the 1815 Club, Theresa’s, the Blue Flame Lounge — on every other corner. Some were no more than tiny rooms that could fit 35 people if no one took a deep breath.

There were so many clubs, Mr. Guy said, “you couldn’t count them all.”

One reason the clubs thrived, he said, was because “back then, everybody had a job.” People could afford to go out, and everybody wanted to hear the famous Chicago blues.

“When the Beatles started, they came here,” Mr. Guy said. “When the Rolling Stones started, they were on 21st and Michigan, trying to find Chess Records.”

Those days are long gone. The relocated Legends, which opened its doors on May 28 at 700 South Wabash Avenue, is one of the city’s few remaining venues dedicated to live blues. Mr. Guy hopes his club will provide emerging blues musicians with the kind of exposure he got playing at the 708 Club and the Blue Flame.

“If there wasn’t a club when I came here, nobody was going to see me walking down 47th Street and say: ‘There goes Buddy Guy. One day he’s going to be a guitar player,’ ” said Mr. Guy, an energetic 74. “I had to go into those clubs and play.”

Lincoln T. Beauchamp, known as Chicago Beau, is a musician, magazine publisher and author of a book about the city’s blues history. The blues community that once flourished on the South and West Sides, Mr. Beauchamp said, fell victim to changing social and economic conditions.

“Pre-integration, the black community was a lot more vibrant,” he said. “Along 47th Street and Cottage Grove, you had a community that was able to sustain itself, and the blues and jazz clubs were part of it, not just socially but also politically.”

“Now, as gentrification takes place and the neighborhoods crumble,” Mr. Beauchamp said, the social fabric changes and the clubs disappear. “You’ll probably never again see the same kind of deep, soulful pulse coming from the neighborhoods, because the neighborhoods aren’t there anymore.”

For the most part, Mr. Beauchamp said, younger black musicians are not drawn to the blues. “They’re not completely detached from it,” he said, “because it’s part of who we are. But it’s just not what inspires them.”

Bruce Iglauer, president and founder of Alligator Records, a major blues and roots record label, said he had watched the blues in Chicago become a tourist attraction — sanitized, prepackaged music for “middle-aged white people who discovered it during college,” he called it.

Blues players and their fans are aging, Mr. Iglauer added, and they are not being replaced.

“Chicago radio stations don’t play the blues, so young people aren’t hearing it anywhere,” he said.

Although he gives the city credit for continuing to back the Chicago Blues Festival, the annual three-day series of free performances that begins Friday in Grant Park, Mr. Iglauer said the city could be doing “so much more” to support club owners.

The day before opening night, Mr. Guy showed off his club to Mayor Richard M. Daley, who stopped by for a tour and to pay homage to Mr. Guy.

“People come here and the first thing they want to do is hear the blues,” Mr. Daley said. “That’s the big selling point. They come from all over the world — heads of state, diplomats.”

Growing up in Louisiana, Mr. Guy was a teenager when his family got a phonograph. He then saved up and sent away for the 78 r.p.m. records of the songs he heard on the radio.

When he came to Chicago, Mr. Guy could play the guitar — “one or two licks” — but he had chosen the city for its promise of steady work and good pay. The music, he said, was secondary.

At night, however, he went to blues clubs and watched his heroes strut the small stages, lamenting lost loves and hard times. One day, he said, “they were asking me to play with them.”

Five decades later, he is still playing an international festival circuit that would exhaust most people half his age. But Chicago is home.

“When I got here, it was September,” Mr. Guy said, “and the birds were flying south, back to Louisiana and Texas and Florida. And I told the birds, ‘You’re smarter than I am.’ ”

Then he started working with the city’s top blues players.

“And now they’ve all left me here,” he said. “Someone’s got to carry on.”

|

2010 Kansas City Kansas Street Blues Festival Forced to Cancel

|

Kansas City, KS, May 28, 2010—The festival dates were set for June 25th and 26th, 2010, which would have been the 10th annual celebration. But, because of a new Kansas statute and a Wyandotte County-Kansas City, KS, revenue-oriented ordinance, after nine successful years of our festival being a BYOB free event, it is considered illegal to drink on sidewalks, streets, alleys or public right-of-ways—festival or no festival. Bringing in your own cooler is now the root of the legal trouble for the demise of the festival. Our festival’s popularity centers on a small town fair, block party, family reunion premise and is not about making money … our festival is about music and the arts. Furthermore, we do not present famous national headliner acts which would support a non-outside beverage event.

The KCKStreet Blues Festival began at Third & Parallel in the northeast district in 2000, “dressing it up in the neighborhood” and bringing the musicians and the community back to their roots. We have had nine successful years in the northeast district which has helped give birth and nurturing to the blues and jazz of our city. Some of our key indigenous artists who have made this festival exceptional include: Lawrence Wright, Provine “Little” Hatch, King Alex, Millage Gilbert, Ida McBeth, Anetta “Cotton Candy” Washington, Myra Taylor, Diane “Mama” Ray, Linda Shell, KC Kelsey Hill, Sonny Kenner, The Scamps, DC Bellamy, Bill Carter, Danny Cox, Lester “Wizard” King, Bobby Watson, Marva Whitney, Eugene Smiley, Blues Notions, Richard Townsend, Everette DeVan and Jay McShann. Over the years, the festival has also presented significant national treasures who are not necessarily considered household names like David “Honeyboy” Edwards, Henry Townsend, Lazy Lester, Bobby Rush, Chick Willis, Eddie C. Campbell, Willie King, Texas Johnny Brown and Louisiana Red.

Over 20 Lifetime Achievement Awards have been presented. Each year, the festival honors a king or a queen as part of its celebration which brings pride to the community of artists and its fans. Additionally, the festival presents memorial tributes and remembrances each and every year. The goal of the festival is to bring all races together, on a grass roots level, and focuses on musicians who were born, raised, lived or have performed a significant number of years in the Kansas City, KS, community. This festival is a positive cultural event that survives year after year on a bare bones operating budget.

The Street Blues Festival entertains visitors from almost every U.S. state and most of Europe, Australia, Canada, Malaysia, Korea and Japan. The festival draws attendees primarily from the metropolitan and regional areas. Recently, the Kansas City, Kansas–Wyandotte County Convention and Visitors Bureau “Tourism Event of the Year” award was presented to the 2009 Kansas City Kansas Street Blues Festival. Our festival has received many honors, the most prestigious being funded by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2003 and 2005. The blues “Who’s Who” for the past decade has dubbed the Kansas City Kansas Street Blues Festival as a “critics choice blues festival—unassuming, honest and real.”

Again, regrettably, the 2010 free festival has been forced to cancel due to change in state statute and city/county ordinance. Key decisions by city/county officials could not be solved in a timely manner to allow the fest to go on as scheduled for this year. It’s our hope that the governing bodies will come together with a new understanding which allows our festival to continue for 2011. With this in mind, June 24th and 25th, 2011, will give us the opportunity to hold our 10th extended almost annual celebration of a thriving blues heritage … at its current location—13th & State Avenue in Kansas City, KS.

|

BLUES FOUNDATION AUCTION

|

| June’s E-bay auction item features 2010 Blues Hall of Fame inductee Charlie Musselwhite. Maybe you saw Charlie recently on Donald Trump’s The Celebrity Apprentice performing with Cyndi Lauper on her new single "I'm Just Your Fool" from the album Memphis Blues. Well, maybe you saw it later on YouTube.

This month’s offer is a performance shot of Charlie printed on 20 x 24 canvas in a black wooden frame. The original photo was taken by Dusty Scott and the presentation has the look and feel of a painting. It is autographed by Charlie in silver. Harp fans, Charlie fans—this is the ticket! Bidding is open now and it starts at a low, low introductory price of just $150. All proceeds benefit The Blues Foundation. Click here to bid.

|

New TV series (almost) Goes To Memphis

|

(Mitch McCracken/The Sun-Times)

Memphis Beat centers on Dwight Hendricks (Jason Lee), a quirky Memphis police detective with an intimate connection to the city, a passion for blues music and a close relationship with his mother.

He is “the keeper of Memphis,” a Southern gentleman who is protective of his fellow citizens and deeply rooted in its blues music scene.

Memphis Beat was created by Liz W. Garcia (Cold Case) and Joshua Harto (The Dark Knight), who also wrote the first two episodes.

Harto, who grew up in the South and has spent a lot of time with his country-musician grandfather, sees the show’s setting as a chance to spotlight one of America’s great cities.

Music is just as vital to Memphis Beat as its unique characters, drama and humor. “Music is a huge part of this show,” Garcia says. “It has to be. You can’t live in Memphis and not have your life steeped in music. The city has a soundtrack.”

To get that perfect Memphis feel, the production team approached noted blues singer/songwriter Keb’ Mo’. He will provide original compositions and performances for the show to supplement classic Memphis tracks.

I had a chance to interview Jason Lee about his new TNT series; here is some of what he had to say.

Q: What is it about this show and the character that appealed to you and made you want to be part of it?

Jason Lee: Well on the surface it was clear that it was very different than anything I’ve ever done. That was a big part of it and then the fun of getting to play a detective and certainly the fun of getting to play a detective who also performs the music of Elvis on stage.

Q: You mentioned the Elvis connection and music is a huge part of this show. So tell me just a little bit about your performances on there and the practice that went into it?

Jason Lee: Well there was a lot of practice. I’ve performed a few times now because we’re five episodes into the first season.

It’s a side of Dwight that is as important to him as his detective work and the burden of protecting his city and those around him and his family.

It’s just fun to kind of just stop and think wow who knew after Earl got cancelled that I’d go from that to playing a detective and singing Elvis songs on a stage in Memphis.

Q: I wanted to ask you now about the singing. Was that a big challenge for you?

Jason Lee: Well I hate to burst your bubble but my voice didn’t quite cut it when we first started recording and so somebody else had to step in but I’m sure glad it looks right.

Q: How did you feel about that?

Jason Lee: It’s the show working or not is what’s important. I mean certainly I would like to be doing the singing myself. It’s my job to make it feel right.

Q: When you started, the show was called Delta Blues. Do you have a strong feeling about that one way or the other?

Jason Lee: Well I really liked Delta Blues. Memphis Beat grew on me and we’re kind of in our own way making somewhat of an old school cop show and so I think Memphis Beat sort of feels like it could have been a cop show from the 70s which is cool and I like. It lets you know that it’s a cop show pretty clearly whereas Delta Blues you may not know straightaway.

Q: You said you did a lot of the recording in New Orleans. How much of the filming is done in Memphis?

Jason Lee: A little bit, we’re going to Memphis every couple of weeks to get some key scenes we need to get up there. But most of it’s done here in New Orleans.

Q: Are the club scenes shot in New Orleans or in Memphis?

Jason Lee: We’re actually shooting right now at the famous Tipatina’s in New Orleans.

That’s actually where we shot the pilot, the performance that I do in the pilot, we shot that right here in New Orleans.

While the series is set in Memphis, it isn’t filmed there. There are a lot of Memphis transplants here in Heber Springs that can understand why. The blues and Elvis make it appealing, reality doesn’t.

You can catch Memphis Beat Tuesdays at 9 p.m. on TNT starting June 22.

|

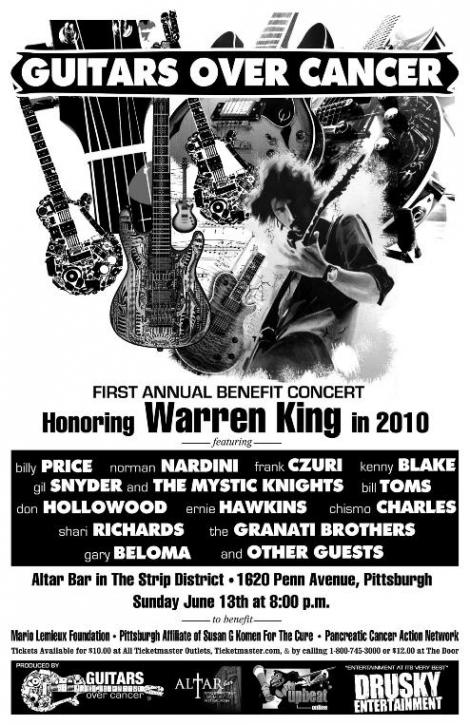

“Guitars Over Cancer”

|

| PITTSBURGH MUSICIANS COME OUT FOR THE LATE WARREN KING.

Mr. Lee, a radio dj and producer, has created the 1st annual “Guitars Over Cancer” benefit concert, to raise money for cancer charities. Lee, and musician Gil Snyder, are producing the benefit concert, along with other friends of “the Kingfish,” to be held Sunday June 13, 2010, 8pm, at Altar Bar in the strip district of Pittsburgh.

The annual concert will always honor another person who has fought the good fight, and has left an impact on our great city. An honoree also may be someone in the midst of their arduous battle.

This first year we honor legendary Pittsburgh guitarist, Warren King, the Kingfish, who died from liver cancer in January. In his honor and certainly his memory, donations will be made to the Susan G. Komen For the Cure, the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network and the Mario Lemieux Foundation.

There will be auctions and raffles throughout the evening with items from the Pittsburgh Penguins, Blues Festival, SportZburgh, Marriott, and more, as well as some film clips of Warren King and friends from the past decades.

Donations at Ticketmaster are $10 in advance, and $12 at the door. Produced in association with Brian Drusky Entertainment.

Please support “Guitars Over Cancer.”

|

I HEAR AMERICA SINGING: THE BLUES

|

| Cantatica, a choral group that's been active in the Lehigh Valley under the direction of Dr. Michael Tamte-Horan for the past three years, has put together a remarkable program of vocal and instrumental works for Sunday afternoon in St. John's Evangelical Lutheran Church in Allentown.

The program is titled "I Hear America Singing: the Blues" but the scope of the music is quite a bit broader than that. For example, not only is there a selection of vocal blues numbers and a bit of traditional gospel —"On the Battlefield for my Lord" — but some instrumental music based on blues ideas.

Specifically, Philadelphia violinist Hanna Khoury will perform two duos with piano by 20th century American black composer William Grant Still, who wrote in a quite traditional classical style.

Some of the selections are for soprano solo, including some arrangements of gospel music by John Carter, and Philadelphia opera star Toni Marie Palmertree will perform these. She'll also sing Louis Armstrong's Basin Street Blues, accompanied by male choir.

A male quartet, accompanied by percussion special effects, will perform four songs from a genre that's a bit unusual, the "chain-gang" song.

These songs have been adapted from a 1950's ballet "Rainbow 'Round My Shoulder" by Milton Okun and Robert DeCormier.

Palmertree will be joined by clarinet, violin, bass and piano for a selection of songs setting poems of Langston Hughes by Broadway and opera composer Ricky Ian Gordon.

Tamte-Horan says this program is part of a series of theme concerts, which have been under the heading "I Hear America Singing." Other Cantatica concerts have featured Celtic and Jewish music.

Cantatica has successfully broadened the scope of choral, vocal and instrumental music in the Valley. It also has been supporting young and emerging professional musicians.

• Cantatica, 4 p.m. Sunday, St. John's Evangelical Lutheran Church, 37 S. Fifth St., Allentown. Tickets: $10-$14. 484-951-5113, www.cantatica.org.

|

Paulie's Nola Jazz & Blues Festival

|

| July 16 & 17, 2010 - Rain or Shine

John & Son's Fairgrounds - 226 Chandler Street - Worcester, MA.

Friday: 7pm - 11 pm - festival gates open @ 5:30 pm

Saturday: Noon - 11 pm

Festival Performances Include:

~ Anders Osborne ~

~ Village of Piedmont Cajun Fiddlers ~

~ The Hurricane Horns ~

~ The Delta Generators ~

~ Emmanuel Baptist Church Gospel Singers ~

~ The Flutie Brothers Band ~

~ The Love Dogs ~

~ Dr. Gonzo's Uncommon Condiments Roadkill Orchestra ~

~ Henri Smith New Orleans Friends & Flavours ~

~ Holmes ~

|

6th ANNUAL HOT BLUES AND BBQ JUST ONE WEEK AWAY

|

| Hot Blues and BBQ, the Village of Oxford, the Oxford Downtown Development Authority, and the Detroit Blues Society are proud to announce that the 6th annual HOT BLUES AND BBQ will be held June 17-19, 2010.

• The Thursday, June 17th event will be held from 7pm-9pm in Centennial Park in Downtown Oxford, MI

• The Friday, June 18th event will be held from 7pm-10:30pm in Centennial Park in Downtown Oxford, MI.

• The Saturday June 19th event will be held from 12pm to 12:30am, in beautiful Scripter Park, in the Village of Oxford, Michigan.

The festival has returned to a 3-day format after several years of tinkering with several different combinations. According to festival producer, Steve Allen, the three-day timeframe gives the Village and the event a larger period for maximum exposure. Again this year all events on all 3 days are absolutely free of charge for admission. This is being done again this year due the continuing poor state of the Michigan economy and to allow families a weekend of fun without the worries of money. Close-in parking will be $5 on Saturday.

THE THURSDAY EVENT

The Thursday Night Event is combined with Oxford’s weekly “Concerts in Centennial Park” Series, will feature Blues rocker, Randy Brock, and admission is absolutely free. Time is from 7pm-9pm.

THE FRIDAY KICKOFF EVENT

The Oxford DDA Kickoff Night will feature Blues performances from 3 regional acts, all of which are well known in their own right. The park will open at 6:00pm and admission is absolutely free. Food will be available on premises as well as all over downtown. The musical lineup for this event will feature (along with their performance times):

• THE ROBIN MOORE BAND (7:00pm)

• THE JAKE BISHOP BAND (8:00pm)

• THE ALLIGATORS (9:00pm)

Immediately following the performances there will be a KICKOFF PARTY at Casa Real (2 doors north of the park) and will feature The Front Street Blues Band. This event is absolutely free.

THE SATURDAY EVENTS

THE 2010 DETROIT BLUES CHALLENGE

The Detroit Blues Challenge at Hot Blues and BBQ is the 4th preliminary round of the annual Detroit Blues Society Challenge where the overall judged winner will move on to the Challenge Finals in October. In 2009, 6 preliminary rounds were staged plus the Finals. In 2010, there will be 4 rounds plus the Finals. The overall winners of the Finals will go on to represent Detroit at the International Blues Challenge in Memphis, Tennessee in January of 2011.

In this, the 3rd round of the Blues Challenge, the competitors will be (along with their performance times):

• THE HATCHETMEN (12:00pm)

• G’JAI’S JOOK JOINT (12:30pm)

• THIRSTY PERCH BLUES BAND (1:00pm)

• CIDY ZOO (1:30pm)

Each Band will play 1, 20-minute set of original music, and will be judged by a panel of music professionals, in accordance with International Blues Challenge rules, to determine an overall winner of this round. The winner will be announced at around 2:00 pm.

There will also be a people’s choice award for the crowd’s favorite band. Patrons will vote with dollar bills and the band with the highest total of votes will win. All monies raised will benefit the Detroit Blues Society’s Blues Challenge Prize Fund. The Detroit Blues Society is a registered 501c3 charity and all donations are tax deductible.

HOT BLUES AND BBQ MAIN EVENT

Hot Blues and BBQ 2010 will feature spectacular Blues performances from a star-studded cast of musicians from across the state of Michigan. Along with the musical performances, the event also features BBQ Vendors, the Hubert Distributors - Bud Light Beer Garden, Retail Vendors, Swimming, Picnicking, a Playground, Raffles, and an entire day of family fun for all. The gates will open at 11:00am and admission is absolutely free.

The musical lineup for 2010 looks like a who’s who of Blues music and will feature (along with their performance times):

• LESTER’S BLUES (2:00pm)

• JAM SAMICH (3:00pm)

• KATHLEEN BOLTHOUSE BAND (4:00pm)

• CROSSROADS BLUES BAND (5:00pm)

• THE FLYING LATINI BROTHERS (6:00pm)

• RUSTY WRIGHT BAND (7:00pm)

• DAVID GERALD BAND (8:00pm)

• BROKEN ARROW BLUES BAND (9:00pm)

• THE BOA CONSTRICTORS (10:00pm)

• MOTOR CITY JOSH AND THE BIG 3 (11:00pm)

|

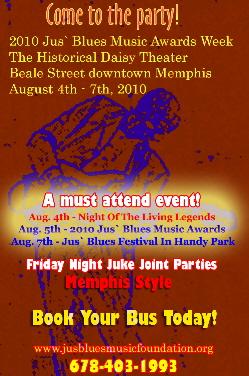

2010 Jus` Blues Music Award Week

|

| Night of the Living Legends - August 4th, 2010 - 7pm - 11pm * Historical Daisy Theater

A formal dinner entertainment event in celebration of the 2010 Jus` Blues Music Awards Honorees.

Technology Conference - August 5th, 2010 10am - 4pm - Theme: "Blues Got A soul"

This is a must-attend event for music technology students, professionals and artists interested in promoting, marketing and driving sales via new technologies.

2010 Jus` Blues Music Awards - August 5th, 2009 7pm - 11pm * Historical Daisy Theater

The pre-eminent entertainment Blues & Soul Music Awards ceremony acknowledging the accomplishments of some of the brightest artists, radio personnel and industry professionals in the genre of Blues & Soul music from popular votes from the www.jusbluesmusicfoundation.org website.

Jus` Blues Juke Joint Club Crawl Memphis Style Friday Night!

In conjunction with the sponsors, supporters, members, musicians and the fans, the JBMF will host a concert party to the public featuring many of the artists from the 2010 Jus` Blues Music Awards.

|

MISSY ANDERSON:

It’s a Radio Hour soul attack! Elwood introduces to you a new diva out of San Diego, by way of Detroit and New York: Missy Andersen. Elwood will spin her tasty old school soul music, plus that of the players who influenced her: Etta James, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Freddie King, Candye Kane…. There is also new music from blues rocker Nick Moss, and a chance for you to win Joe Bonamassa’s new album, BLACK ROCK, and tickets to Pennsylvania’s Briggs Farm Blues Festival. Right here.

For a list of stations where you can find House of Blues Radio

|

|

|

| Click on festival name to click through to festival website. |

VISIT THE BLUES FESTIVAL GUIDE WEBSITE FOR ALL THE FESTIVALS

Over 500 festivals are listed on the website www.BluesFestivalGuide.com |

Tinner Hill Blues Festival

Thursday-Sunday,

|

Mijas International Blues Festival

Thursday-Sunday,

|

Barrie Jazz & Blues Festival

Thursday-Monday,

June 10-21, 2010

Barrie, Ontario, Canada

www.barriejazzbluesfest.com |

Greeley Blues Jam

Friday-Saturday,

June 11-12, 2010

|

Bricktown Blues & BBQ Festival

Friday-Saturday,

June 11-12, 2010

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S.

www.bricktownokc.com |

Virginia Blues & Jazz Festival

Friday-Sunday,

|

Chicago Blues Festival

Friday-Sunday,

June 11-13, 2010

|

Strawberry Valley Blues Festival

Friday-Sunday,

|

Texas Folklife Festival

Friday-Sunday,

|

Thirsty Ear Festival

Friday-Sunday,

June 11-13, 2010

Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.

www.thirstyearfestival.com |

River and Brews Blues Fest

Friday-Saturday,

|

State Street Blues Stroll

Saturday,

June 12, 2010

Media, Pennsylvania, U.S.

www.statestreetblues.com |

Famous Dave's BBQ & Blues Festival

Saturday,

|

Solo Soul and Blues Festival

Saturday,

|

Ashvegas Blues Festival

Saturday-Sunday,

June 12-13, 2010 Asheville, NC, U.S. Website |

W. C. Handy Blues & Barbecue Festival

Saturday-Saturday,

|

Billtown Blues Festival

Sunday,

|

13th Annual BBQ RibFest

Thursday,

|

Hot Blues & BBQ

Thursday-Saturday,

|

Smokin' On The River

Friday-Saturday,

|

The Second Annual Lake Cumberland Blues, Boats and BBQ Fest

Friday-Saturday,

|

T-Bone Walker Blues Fest

Friday-Saturday,

|

Blues On The Fox

Friday-Saturday,

June 18-19, 2010 Aurora, Illinois, U.S. Website

|

Canton Blues Festival

Friday-Saturday,

|

Hambone Blues Jam Music Festival

Friday-Saturday,

|

Creekside Blues and Jazz Festival

Friday-Sunday,

June 18-20, 2010 Gahanna, Ohio, U.S. Website

|

Live Oak Music Festival

Friday-Sunday,

|

Maine Blues Festival

Saturday,

|

8th Annual Blues Picnic

Saturday,

June 19, 2010

Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.

Website

|

|

|

RBA Publishing Inc is based in Reno, NV with a satellite office in Beverly Hills, Florida. We produce the annual Blues Festival Guide magazine (now in its 7th year), the top-ranking website: www.BluesFestivalGuide.com, and this weekly blues newsletter: The Blues Festival E-Guide with approximately 20,000 weekly subscribers. We look forward to your suggestions, critiques, questions, etc.

Reach the E-Guide editor, Gordon Bulcock, gordon@bluesfestivalguide.com

or contact our home office at 775-337-8626, eguide@bluesfestivalguide.com

back to top

back to top

|

| Information - both editorial and advertising - in the Blues Festival E-Guide - is believed to be correct but not guaranteed - so check it carefully before you attend any event or send money for anything. We do not write the news... just report it. |

|

|

|

| |

|